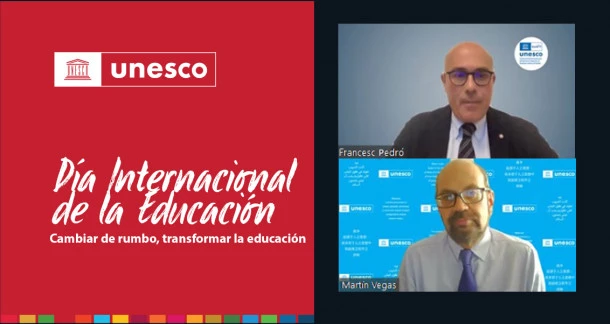

Francesc Pedró: “If you have to define the purpose of university autonomy, it is very important that it be done from an agency that is not captured by the sector”

Francesc Pedró is Director of the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC). He was interviewed by Martín Vegas, coordinator of the UNESCO Horizons Program in Peru, to contribute to the debate on the changes proposed in the Congress of the Republic of Peru on key aspects of quality assurance in higher education.

A first aspect that we would like to ask is about the importance that quality assurance has gained in higher education. Since when are these systems implemented?

Thank you very much for this opportunity to shed some light on the current debates on quality assurance in Peru, in the region and internationally. It is a really very important issue for UNESCO.

Quality assurance procedures are relatively recent. In our region, we are talking about two decades. At present, it could be said that there are practically no countries with a medium or high-middle income level that do not have quality assurance procedures. It is the most efficient way that has been found to manage the explosion in demand for higher education and to attend to the emergency that originated from a series of university offers that took place without any type of supervision or regulatory framework.

From UNESCO’s perspective, quality assurance processes are important in themselves, because they must help us understand that the effort to achieve the universal right to higher education without guaranteeing a minimum of quality for all people is, in reality, distorting the provision of higher education.

For UNESCO, it is also a way to advance the agenda of equity and inclusion in higher education, ensuring that we effectively protect the rights of students, their families, and in doing so, the strategic interests of our countries as well. Therefore, it is not strange to talk about quality education with equity and inclusiveness throughout life because, one way or the other, we need to strengthen the mechanisms through which we govern quality, which is, ultimately, a way of also intervening on equity.

To ensure quality, we have mechanisms for minimum and mechanisms for excellence. In Peru, licensing and accreditation are sometimes confused. How are these schemes organized?

Indeed, it also happens internationally. In fact, you have a country close by, which is Colombia, where the recognition of the suitability of an institution to provide higher education, that is, the guarantee that there is a minimum -for example, of facilities, and above all, of the academic competencies of the teachers- is a first step from which the country can allow itself to enter into a much more complex discussion about what excellence is or, as they call it in Colombia, “high quality” and how to promote it.

Therefore, we must distinguish between these two things: the first, which would be to guarantee that every institution or, if you prefer, every program that is taught, complies with some basic minimums. This is, really, a measure to guarantee the right to quality higher education for each and every one of the students. With this we are guaranteeing that, thanks to a regulatory intervention carried out by an intervening agency, everything that a university offers meets minimum requirements. This is different from trying to ensure that the entire system as a whole continues to progress to reach the level of excellence that we would all like to see as a universal heritage, but which logically requires a much longer-term journey.

Consequently, licensing is a basic element in protecting the rights of citizens to have access to what UNESCO considers to be a public and social good, which is higher education. But, the second very important task of this type of agencies is to promote the constant improvement of quality and for that we need to be certain that this type of agencies -like SUNEDU or CONEAU in Argentina or CNA in Chile and so many others since there are only a couple of countries in Latin America that do not have an equivalent to a specific agency- are staffed by technically qualified personnel who do not represent any other interests than the interests of quality and academic excellence.

Is there any evaluation or way of knowing if the licensing generates or has generated any benefit or impact?

A first element is to observe the extent to which higher education systems in our region and in other regions with similar levels of development, such as part of Asia and even part of North Africa, have managed, if I may use the expression, to “sanitize” provision, that is, to reduce the number of institutions and programs as a result of a process of assuring minimum quality standards. This is basically an indication that pressure has been exerted to ensure that, through a clearly selective process, only those which the country considers should survive, do so.

A second indicator of the relevance of these processes is the fact that international and regional networks that guarantee a convergence of criteria are beginning to exist. The idea is that a program that is approved in Chile should be approved with the same guarantees that would apply in Argentina, Mexico or Bolivia. UNESCO is very interested in guaranteeing the internationalization of higher education systems and this requires for the concept of quality in higher education to have an increasingly shared definition in all the countries of the region. Some Peruvian organizations are already involved in these networks. This effort on convergence is indicative of the fact that the problems and solution routes in the region are very similar.

A third element is data showing that, in the countries of the region, such as Peru, access rates are improving. Some people will probably think that there is no better way to promote access to higher education than not putting “doors to the field”, that is, to let everyone offer programs and create institutions, and that this promotes the democratization of access; but this is a misrepresentation of reality. What has been observed is that despite the fact that the number of institutions has been slightly reduced as a result of the pressure to guarantee a minimum of quality, access rates have continued to improve, and what is more important, is that graduation rates have also improved and have done so at a higher rate than access rates, which is indicative of the fact that the cleaning up of the system has made it healthier, that is, of higher quality.

The evaluation of the results in terms of reduction in the number of institutions, the increase in access rates and at the same time the improvement in graduation rates are indicative that, indeed, a policy of quality assurance is far from being contradictory to a policy of democratization and universalization of access to higher education; and at the same time it can achieve a much more relevant and pertinent offer. Basically, we must be concerned about the extent to which the entering student has a chance of success, and this has a lot to do with the quality of the processes of which he or she will be a part during his or her stay in the higher education institution.

A point that generates much debate in the case of Peru is university autonomy. Some consider that university autonomy would be affected if the State is in control of the regulatory body. Do these models in which there is a regulatory or supervisory body affect university autonomy, and are there ministries in the world that have responsibility for higher education?

Let’s start with the easiest one, which is the second question. Our institute published a note a few months ago on the occasion of the reform of the structure of the Peruvian Ministry of Education in which we made it clear that, as higher education systems gain maturity, they also have increasingly specialized structures within the ministries. In very few cases we have ministries of higher education, as in the cases of Cuba, Venezuela or the Dominican Republic, but in most countries we have vice ministries that deal with higher education and this allows the State to have greater room for maneuver.

In this sense, one of the things that most justifies having a ministry or vice-ministry of higher education is the fact that, unlike the school sector or technical and professional training, higher education institutions, and in particular universities, have always been characterized by a high level of functional autonomy. This autonomy has to do with their capacity to decide which are the lines of research, which are the works they are going to undertake and even the way in which they are going to teach their courses. It is worth noting that, in the case of public universities, autonomy is a direct function of the funding capacity they receive directly from the State.

Therefore, when quality assurance programs are created, what is basically being done is to try to establish the parameters that currently define what is a quality university provision; but, of course, the level of detail will never go to the extreme of restricting university autonomy. I am going to give some examples, which are the result of an international consensus: When we talk about the academic quality of a university, we count, for example, how many professors have postgraduate training, how many have a doctorate, and how many have a funded research program. It seems to me that this is so obvious that, evidently, whoever says that establishing parameters means curtailing academic freedom is, at bottom, confusing things. An important question is who defines what a university is today. Quite simply, it is the university context itself that demands a series of parameters such as those I have enunciated, and many others of greater complexity.

The final objective of the discussion on university autonomy is not to guarantee autonomy as a universal good, but to remember that autonomy is placed at the service of the supreme interest of the promotion of science and knowledge, through training and research. If there comes a time when it is necessary to define exactly the purpose of autonomy, it is very important that it is done from an agency that is not captured by the sector because that is one of the fundamental risks that, fortunately, in most of the countries of our region have been avoided. The risk is for the agencies to become, no more and no less, the voice of the provider universities themselves. This is what we call regulatory capture, that is, that the very subject that is to be regulated controls the regulatory body. Then there would be no way to progress, we would always remain protecting, not the interest of the student and the family, but the interest of the institution or the corporation behind an institution.

The region has shown itself to be absolutely faithful to this criterion of independence that avoids regulatory capture by the sector itself. There are published articles that compare the level of political autonomy of the agencies and it is very important to highlight that, so far, Latin American agencies are characterized by a level of political autonomy equivalent to, and in some cases, even higher than that of Western European agencies. This seems fundamental to me because it means that we have been able to establish, in most of our countries, agencies based on the criterion of independence, on extremely professional, scientific and academic criteria. I would not like to give the impression that there are no problems, because there are, but I would like to say that if anything characterizes the programs and agencies we have in the region, including SUNEDU in Peru, it is rigor and quality from the professional and technical point of view, from the academic point of view, while at the same time asserting independence.

The Peruvian scheme of SUNEDU is that the board is made up by members of the university community, but by public merit-based competition. How could it affect, in addition, having an appointee from the Ministry of Education and another from CONCYTEC?

To make it very clear, the procedure currently used in SUNEDU is the most frequent procedure, not only in Latin America, but in the whole world. That is to say, what we are trying to do is to guarantee the presence of the State, but in a context in which most of the seats obey a criterion of academic and professional capacity, that is, they are people who are there based on a series of merits they have accumulated because they have distinguished themselves in the field of research and training; because they have been part, on more than one occasion, of what would be great projects to improve the quality of teaching. In short, they are there not because they belong to this or that university, not to represent these universities, but they are there in a personal capacity based on the recognition of their trajectory as references in the field of quality in higher education.

Would it be better if these representatives, instead of being the result of a merit-based selection, were appointed by a commission of rectors or perhaps were themselves rectors? I think that would put the discussion on another level. The discussion we have in the programs and in the quality agencies is a discussion about what is the lowest common denominator needed to be able to practice as a university or to be able to offer a program at the higher education level; and, on the other hand, what can we do as a community of specialists to promote the constant improvement of the quality of the institutions and of the programs. This is an independent and extremely qualified discussion from the point of view of the content of the discussion; it is not a political discussion, although it may logically have political implications, as we are seeing.

The role of the rectors, in my opinion, is the role of being the great interlocutors when modifying or promoting new public policies for higher education. And that has to take place in a sphere other than that of the agencies. It could be, as happens in most countries, a Council of Rectors or a Council of Higher Education. It is there where policies should be debated and where the rectors have to put their points of view on the table, but not in discussions about quality, precisely to avoid the risk of regulatory capture, for example, that the same people who have to be regulated are the ones who impose the regulation. Letting the rectors, whom I assume have the best will and are good people, integrate and govern the agency would be as much as creating a cartel. We have seen this in many other places and areas where large providers agree to, for example, fix prices or ensure that regulations protect their own interests. It is good to have an interlocution at the political level, but a quality assurance agency is, fundamentally, as its name indicates, an agency: an instrument at the service of a function on the basis of greater independence and professionalism.

Another point under debate in Peru has to do with the effects of this first licensing. There is a group of students who belonged to unlicensed universities that are affected. So, it is pointed out that quality assurance makes higher education elitist because the poorest are the most affected.

UNESCO’s perspective is that the State’s obligation is to do everything possible so that once a student enters the higher education system, whatever the channel, public or private, he or she has the best chance of successfully completing his or her studies. Therefore, in a process such as the one being experienced in Peru, it is very important to remember that the State has an extremely critical role in terms of regulation to safeguard and protect the right of these students to continue their studies.

Now, if some universities have ceased to be licensed, it is very important to keep in mind that we must provide channels for these students to find elsewhere that training to which they are entitled. It would be counterproductive to think that we should reopen universities that did not measure up in terms of minimum quality requirements. I would like to insist on this, because we are talking about minimum requirements; we are not talking about excellence. So, if we have detected that a number of institutions were not able to pass this threshold and are still far from it, what would be the point of reopening them? Where would the protection of the universal right to higher education be? The right is not the right of access to any type of training, it is the right of access to quality training, and regulating it is an obligation of the State which, here as in most countries, relies on professional and independent agencies to verify it.

Therefore, what we have seen in other countries has been that the States have generated regulatory and funding frameworks that have allowed the relocation of their students to other universities, typically in public institutions, but there are exceptions where students have gone to other private universities that have signed agreements with the State because, sometimes, not all public universities have exactly the same programs that students were following, nor the availability of places required.

Is this going to pass a bill on the country? Undoubtedly, but I believe it is our obligation to deal with it. What is unacceptable is to be told that those universities accessed by students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, not only in Peru, but in many other places, are the only formula by which we can guarantee access to higher education for those strata. This is literally false; moreover, it is the procedure to justify a segmentation of higher education provision where high quality institutions remain out of reach for the most vulnerable students, who have no choice but to settle for a substitute for higher education.

What we have seen happening in many countries, starting decades ago, for example in Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Peru itself, is that there has been a certain stratification of higher education provision. In a study to be published by UNESCO on the occasion of the Regional Conference of Ministers of Education, we show that there are indeed a series of policies that have been introduced in countries with more mature systems to ensure that the essential diversification of higher education does not go against equity, so that it is good to have a diversified system in the sense that there may be universities dedicated to research in certain fields, such as biomedical studies, and others, on the other hand, more dedicated to the social sciences. But it is one thing for the sector to be diversified and quite another for it to be segmented and segregated socially and economically. There is also another very important aspect in higher education, which is everything that has to do with higher technical training, professional technological training, which probably should not be measured with the same criteria as those of research excellence, but which is nevertheless extremely important. Does this mean that the offering has to be of lower quality? No, not at all.

This opens a pending agenda in Peru regarding the implementation of the recently approved policy of Higher University, Technical and Productive Technical Education, considering that we are in a demographic bonus and there is a growing number of students who are finishing high school.

It is very important to make the offer more diversified, because one of the typical problems in our region is that everyone wants to go to university for long-cycle programs, and in reality, what our economies would need, or what the labor markets are asking for, are rather short or medium cycles. But of course, the problem is for this diversification not to translate into social stratification, that is, that this diversification does not end up becoming in turn an engine for maintaining and reproducing inequalities.

What can be said about the solution that existed in Peru years ago to address access based on deregulation, favoring private investment and lowering taxes? Has this route existed in other countries? Is there an evaluation of pros and cons?

That route has already been exhausted. It had its historical moment and, probably, it was a possible route for politically weak or fiscally failed states. It was the simplest solution in a context in which neoliberal policies were rampant in the region, but I believe that stage has already been worn out. UNESCO defends, above all, that the right to the public and social good that is higher education is the fundamental responsibility of the State. The State must guarantee this right and the way to guarantee this right is not by allowing any offer to exist, but by guaranteeing that what is behind the term higher education, in any corner of the country, has a guarantee of minimum quality.

Consequently, these neoliberal policies had their boom, but practically everywhere in the region corrective policies have been introduced, trying precisely to guarantee that the system is cleaned up to ensure that what appears as higher education has an absolutely guaranteed minimum quality and at the same time, to ensure that the higher education system as a whole obeys the interests of the social, economic and political development of the country.

One last question about the rules of the game. In the case of Peru, all the universities applied for licensure with certain standards, most of them have been licensed, but those that were denied licensure are asking for a change in this rule of the game and are waiting for a sort of second chance.

All over the world these rules are permanently changing, but to become more demanding, not less demanding. This is like everything in life, for example, in the world of gastronomy, which is a very dear world in Peru. I imagine that when you are young you start eating only “junk food”, but then, as you get older, you begin to see the difference and appreciate good traditional or modern Peruvian cuisine, right? That is, you educate your own palate. In terms of higher education, during the last 25 years our systems have been maturing and self-educating, so that their levels of demand with respect to quality are increasingly higher. What we see is that the criteria are becoming more and more similar around the world, and at the same time, more convergent and more and more demanding. This is happening because our end users, students, families, our economies and our societies are also becoming more demanding. They are more gourmets, so to speak. If you’ve already tasted something good, you don’t go back.

RELATED ITEMS